Boethius’s presentation requires the historian-detective to offer several observations. First, wanting the senate to be safe and hoping for Rome’s liberty are either meaningless platitudes or else specific political crimes in a context about which we know too little. Second, Boethius does not deny them. Third, the expostulation about the preposterousness of hoping for liberty at this moment in its own way confirms rather than confutes suspicion—for surely the offense lay in suggesting that Theoderic’s regime was deprived of liberty at all.

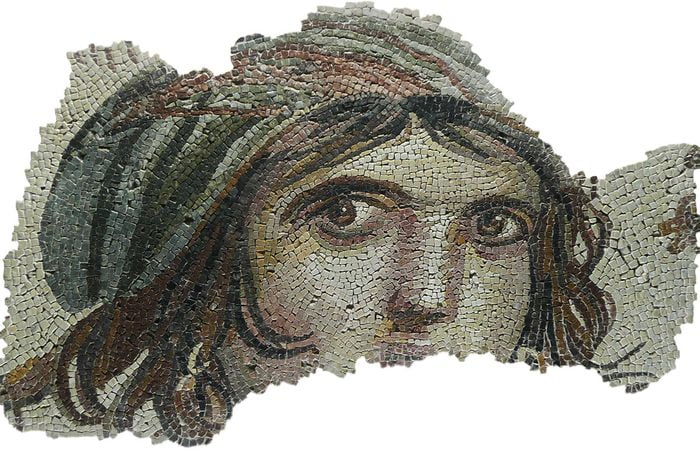

Dramatic stage for us to contemplate

Boethius then sets a dramatic stage for us to contemplate. “You recall” (he tells the allegorical woman called Philosophy, his personification for wisdom itself visiting him in prison to hear and sanctify his lament) “the time the king was at Verona, hell-bent on destroying us all, and how he tried to take the accusation of a crime of maiestas leveled against Albinus and make it encompass the whole senate. And then you recall how I defended the innocence of the whole senate at great risk to myself.”

Apparently that is what has landed him, without trial, in prison, 500 miles from Rome and home, where he wrote his lament. The king suspected treason in his court and Boethius forthrightly defended the suspects—too forthrightly, too persuasively for his own good bulgaria holidays.

Worse is yet to come. Those who seek to destroy Boethius added a charge of sacrilege—that is, of having defiled himself with black magic “out of ambition for high office.” The simple meaning to his contemporaries would be that he had engaged in secret religious rites of the old order (as we saw some of his contemporaries in the senate doing a few years earlier) to advance his own career. Preposterous, he huffs; impossible to imagine the likes of me doing the likes of that!

What can be going on here? The answer is straightforward and not hard to see in Boethius’s own Consolation, although most readers pass right over it. “But you, [Philosophy], approved this remark from the mouth of Plato:32 ‘Republics would be happy if either the philosophers ruled them or if their rulers came to study philosophy.’ ” Boethius goes on to represent that precept as what led him to public life, and I think most readers assume that it justifies a modest entry into upper bureaucracy. The true meaning is too obvious.

Theoderic was not merely paranoid: he had a real enemy. Boethius wanted to be emperor himself—or, more precisely, he wanted to be Plato’s philosopher king.

Boethius

Think of it this way. If you were Boethius, if you were a senior minister at the imperial court of Italy, if you had an impeccable pedigree and the very highest imaginable social standing, and if you saw that the reigning ruler (emperor or would-be emperor Theoderic by Eutharic and Amalasuntha) was nearing his end without a satisfactory heir in place, what would you think should be done or could be done? Who was there that a Roman of this period would think better qualified or better positioned to succeed Theoderic?

And if your neighbors thought you were using black magic to advance your ambitions, what did they think you were aiming for? A one-step promotion to the highest civil office of praetorian prefect? Nonsense: patience and good behavior could get him that. Wouldn’t they assume he was looking at the big step, up to the throne itself?